The National Health Service Corps at 50 Years

One Pagers | Feb 01, 2022

Adrian N. Billings, MD, PhD, FAAFP; Yalda Jabbarpour, MD; and Jack Westfall, MD, MPH

The National Health Service Corps (NHSC) was established in 1970 to address the mal-distribution of physicians in the United States. In 1972, it placed the first clinicians (181 physicians) into rural and urban underserved communities. Since then, the NHSC has grown into a multidisciplinary and racially diverse workforce of 16,000 active clinicians. Despite the program's clear benefits to the primary care workforce and health of vulnerable communities, budgetary constraints limit its reach.

The NHSC was established with bipartisan support by the Emergency Health Personnel Act of 1970.1 Fifty years later, the program has grown into a multidisciplinary workforce of behavioral health professionals, nurse practitioners, physicians, dentists, physician assistants, registered dental hygienists, nurse midwives, and pharmacists with greater racial and ethnic diversity than the national health care workforce.2 Default rates of NHSC participants are very low, and a significant majority of NHSC awardees complete their service obligations.3 Multiple studies have shown short- and long-term retention of NHSC alumni in health professional shortage areas beyond the end of their service agreements.3–5

Today, just as in the 1970s, the NHSC program addresses persistent health care workforce shortages in vulnerable rural, frontier, and urban communities. Most NHSC clinicians work in Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) but also in FQHC “look-alike” clinics, Indian Health Service sites, certified rural health clinics, detention facilities, critical access hospitals, community mental health centers, state and local health departments, school-based clinics, free clinics, and substance abuse treatment facilities.6

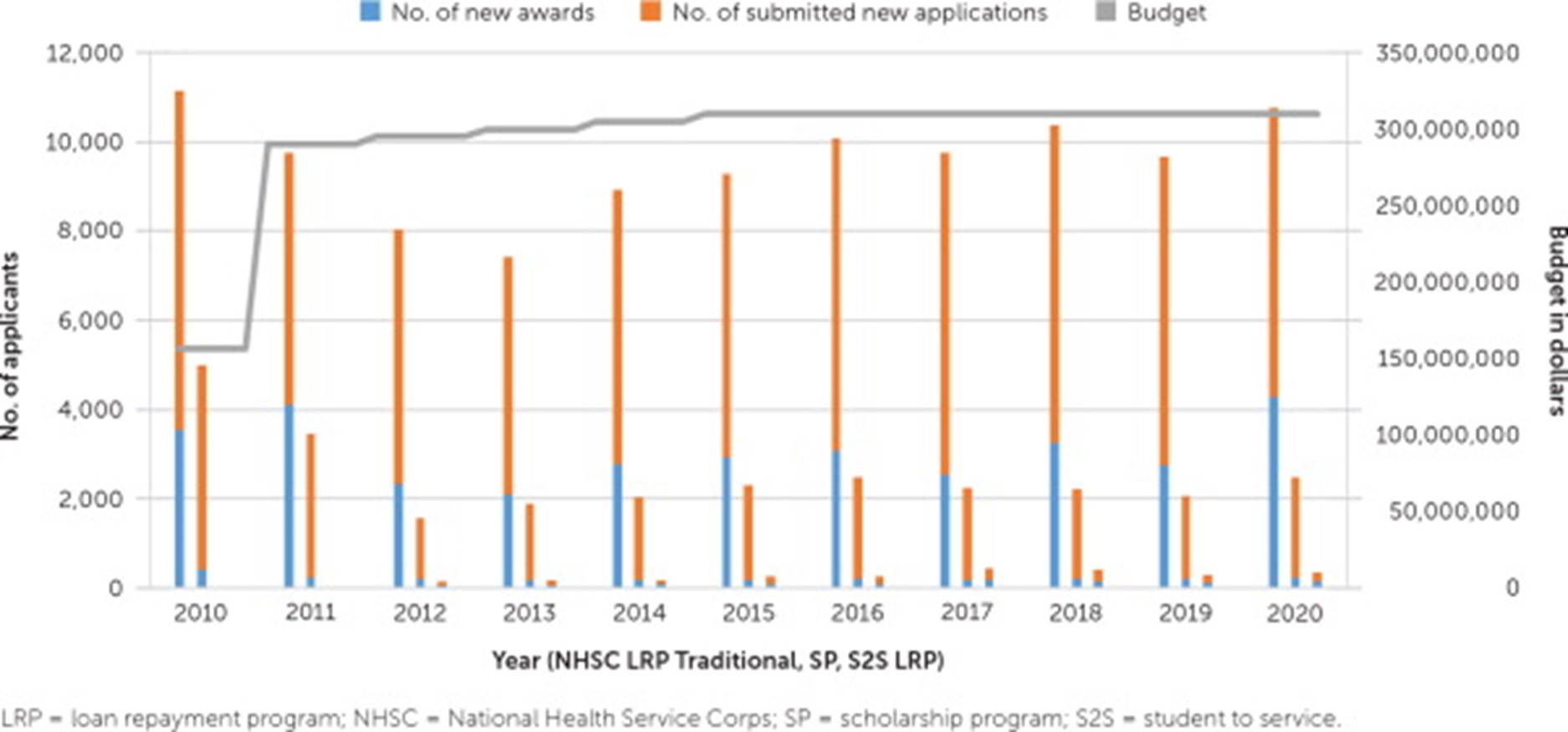

Demand to enter the NHSC programs far exceeds available slots, limiting the full potential of the program to address workforce shortages and workforce diversity in the United States. To examine the gap between funding and demand, we used data from the Health Resources and Services Administration, to overlay NHSC applicants with NHSC funding from 2010 to 2020 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Historical data from 2010 to 2020 showing NHSC program applicants, funded applicants to various NHSC programs with overlying mandatory funding budget. Data from the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Although demand for the program has grown over the past decade (as measured by number of applications), the budget has remained flat. The current NHSC workforce has grown to just more than 16,000 clinicians serving approximately 13.7 million patients annually. Because of budgetary limitations, only 11% of applicants to the NHSC scholarship program, 55% of applicants to the loan repayment program, and 69% of the students applying to service loan repayment programs were funded in 2019.

The United States has a shortage of primary care clinicians. The NHSC is a valuable program that supports a racially diverse workforce for vulnerable communities; however, its mandatory funding support has not increased for the past decade. The demand for NHSC support from students, clinicians and NHSC sites far exceeds what is currently funded by the federal government. Most importantly, patient demand for NHSC clinicians exceeds the current NHSC workforce. Bolstering the inadequate NHSC budget could strengthen the primary care safety net by bringing more clinicians to health centers in underserved communities.

REFERENCES

1. Redman E. The Dance of Legislation. Simon and Schuster; 1973.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National health service corps report to congress for the year 2018. 2019.

4. Pathman DE, Konrad TR, Schwartz R; Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. Evaluating retention in BCRS programs. Final report. March 2012. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Evaluating-Retention-in-BCRS-Programs-Final-Report_Pathman_5-4-12-1.pdf

5. Konrad TR. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the National Health Service Corps: Final Report. Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research; Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.; 2000.

6. Heisler EJ. The National Health Service Corps. Congressional Research Service; April 2018. Accessed December 12, 2020. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44970.pdf

7. National Association of Community Health Centers. Staffing the safety net: building the primary care workforce at America's health centers. March 2016. Accessed December 14, 2020. https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/NACHC_Workforce_Report_2016.pdf

The information and opinions contained in research from the Graham Center do not necessarily reflect the views or the policy of the AAFP.

This series is coordinated by Kenny Lin, MD, MPH, deputy editor.